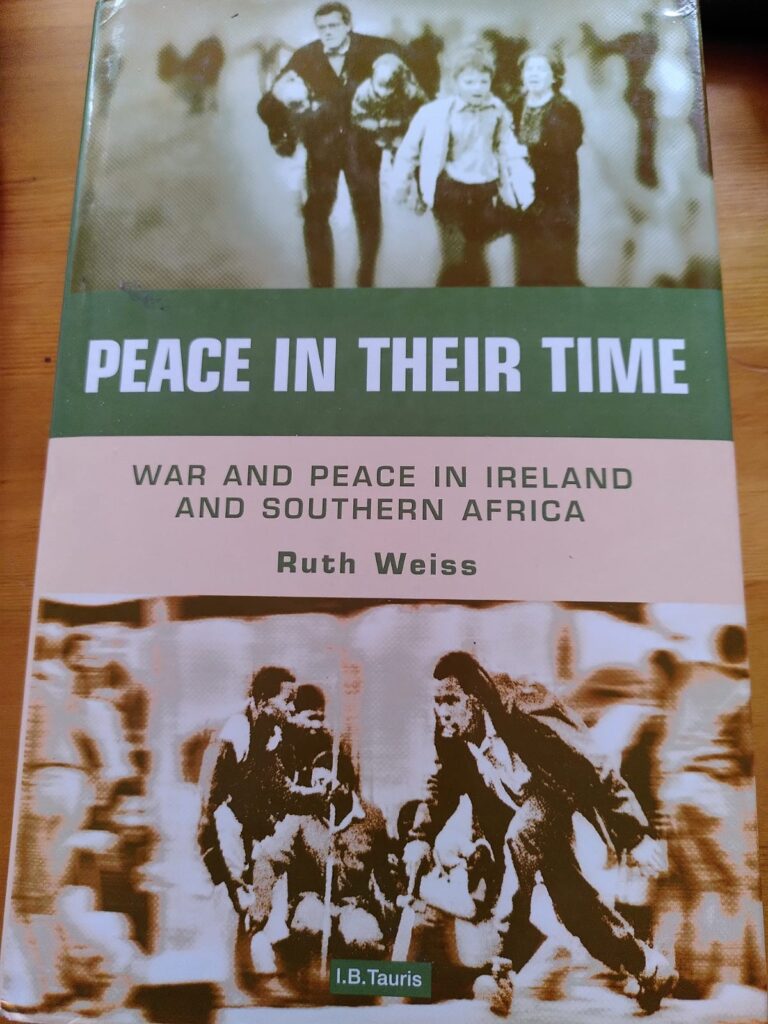

Ruth Weiss

Ruth Weiss – Peace in Their Time

War and Peace in Ireland and Southern Africa

I.B. Tauris Publishers,

London – New York 2000

ISBN 1-86064-403-1; 230 pages

About the book:

Conflict resolution is a difficult and slow process full of false dawns and disappointment. When the roots of anger, hatred and mistrust lie deeply buried in history that history is constantly manipulated to reinforce sectarianism and a sense of past evils. Northern Ireland and South Africa were long considered insoluble problems and both centred around the intractable politics of privilege, communal strife and the domination of one culture over another.

In Northern Ireland, the Protestant majority, comprising some 60 per cent of the population, had held power since the creation of the state as an integral part of the United Kingdom in 1921, based on a domination dating back to the 17b century and beyond. ln South Africa, the white minority had been totally dominant over the black and coloured majority and power was buttressed by a ruthless apartheid police state.

ln Peace in Their Time, Ruth Weiss analyses and charts the tortuous process of negotiation leading to the present flawed but largely welcomed peace in both troubled territories. She describes the halting steps of the learning process, the negotiating skills, control of factions and supporters, surrender and compromise gradually gaining ground, the habit of peaceful life becoming engrained and the very idea of a return to violence rendered impossible.

ln Northern lreland power-sharing and devolved government were hammered out in the Good Friday Agreement with majority support throughout lreland and Britain and fully implemented in May 2000 despite continuing disputes over decommissioning of terrorist arms and the death-throes – often powerful – of sectarianism.

ln South Africa the peace process, begun in the 1980s and based on a long history, achieved a power-sharing government in 1994 followed by the ANC-led government in 1999.

Formidable problems remain but Ruth Weiss’s study, based on face to face interviews and close conversations with leading actors – politicians, journalists, radical and revolutionary groups, even those advocating violence – shows how peace can grow from these seemingly irreconcilable conflicts and how the stop-go peace-building gains irrestible momentum – in Senator George Mitchell’s phrase, ’severe pains‘ can be the birth-pangs of a new society.

Book review

Journal of Conflict Studies Volume 22, Number 2, Fall 2002, p. 161–163 – Extract:

… „A skilled, graceful writer, Weiss is able to guide the reader through the

political convolutions of both peace processes, moving smoothly back and forth

between the two polities to point out similarities and differences and to show, for

example, how the South Africans served to some extent as role models and consultants for the Irish. Both groups had their share of Nobel laureates, the prize

often being shared by protagonists (Mairead Corrigan and Betty Williams in

1976, Nelson Mandela and Frederik W. de Klerk in 1993, and John Hume and

David Trimble in 1998) rather than by a single individual (as was true for Chief

Albert J. Luthuli in 1960 and for Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 1984).“…

Preface of Ruth Weiss :

Everything flows, said the prophet.

This being so, it is not surprising that often mere emblems remain of ideologies long abandoned or labels of political parties, whose policies are unrecognizable from the old. This makes analysis of fluid situations difficult, as in the cases of the end of apartheid in South Africa and the end of IRA action in Northern Ireland, the more so, when placing these situations alongside each other, as I have tried to do. In situations where ethnic groups and politics are linked or overlap, fixed concepts are easily accepted. Yet not every Protestant in Northern Ireland is a hard-line Unionist nor every Catholic a fiery IRA supporter, any more than every white South African was committed to apartheid or every black a fighter for freedom.The ebb and flow of politics ensures that the majority is passive, while pushing the activists to the top.

Communities form the base from which activists operate, and as the will of the majority changes so do the politics. How could it be otherwise? Change is merely a matter of time and generations.

In South Africa actual change, when it came, arrived swiftly. In Northern Ireland the process of change was more intricate, the balance more delicate, and faltered often on the brink of failure. In South Africa the black-white situation made it always obvious that ’non-whites‘ would gain majority rule. In Northern Ireland bitter enmity was more deeply ingrained; the horror of 30 years of conflict was so much part of the present that the process of change took longer. Unionism, feeling itself besieged and betrayed, had to find the courage to overcome its understandable apprehension. Republicanism had to find a way out of the impasse into which violence had led, by deferring but not relinquishing its ultimate aims.

In following the process of change, Northern Ireland won out in terms of emphasis in my pages because of the intricacy, because it was happening when I first visited the island and because it was new to me. Nonetheless it seemed to me that both situations posed similar problems for the communities involved and for their leaders and outside forces.

It appeared valid to look at both as in each country individuals and groups sought desperately to find a peaceful way out of what appeared to be insoluble conflicts based on old, serious grievances and deep hurt on all sides.

Naturally not everyone will agree with me about this view; indeed only a few may do so.